Central Coast Regional Profile

Resilient and Fire-Safe Communities

photo credit: Sashwa Burrows

Overview

Lightning occurs less frequently in the Central Coast region than higher-elevation parts of the state, and moist coastal conditions further reduce ignitions. As a result, the historical fire return interval along the Central Coast would have been in the range of 50 to 100 or more years without the influence of cultural burning. The last major urban fire to occur in the San Francisco Bay Area was the October 1991 Oakland-Berkeley Hills Fire, which caused 25 fatalities and destroyed over 3,000 homes. Over thirty years later, many new residents have moved to the region. Population growth and demand for more housing has expanded the wildland-urban interface, increasing the probability of human ignitions in wildland vegetation and increasing the risk wildfires may impact communities. Land use planning to reduce development in areas of high wildfire hazard, as well as encouraging home hardening practices and the management of defensible space, are increasingly important tools for reducing the risk of fires impacting communities. Renters and residents of multi-family housing may have limited capacity to upgrade their building or manage surrounding property, and regional efforts will need to consider new strategies to help these communities become more fire-adapted.

The August 2020 CZU Lightning Complex fire was a devastating wildfire, caused by an uncommon lightning storm, that demonstrated the intensity and rate of spread potential for wildfires in the Central Coast region, along with the resulting impacts such an intense fire can have on local human communities and natural ecosystems [see ‘Healthy and Resilient Forests’]. As impacted communities continue to struggle with the challenges of rebuilding, there is heightened interest in also making neighborhoods, infrastructure, and natural lands more resilient to future fire. New collaborations with diverse partners have been critical to increasing capacity to work across property boundaries and achieve multiple benefits across the landscape. A prime example of this is the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, which is made up of 24 organizations including diverse agencies, nonprofits, academia, business, community, and tribal groups. These organizations are working together to enhance natural ecosystem functions, adapt the landscape to climate change, and sustainably manage forest resources for future generations.

Similar efforts to facilitate fire-adapted communities are being made in other parts of the region. The Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority and its member agencies are managing vegetation to reduce wildfire hazard, improving evacuation safety, and providing funding and technical support to reduce fire risk on private property. Local agencies such as Resource Conservation Districts are leading and supporting similar projects in counties throughout the region. Community-based organizations such as Fire Safe Councils are also providing public education and mobilizing residents to prepare their homes and neighborhoods against the threat of wildfire.

Additional efforts are focused on reintroducing prescribed fire to the landscape to mitigate the risk of higher severity wildfire. The Central Coast Prescribed Burn Association serves San Benito, Santa Cruz, and Monterey Counties by leading and participating in private-land burning, as well as offering prescribed fire training and public education on home hardening and defensible space. Audubon Canyon Ranch’s Fire Forward program offers trainings and support for prescribed burning in Marin and Sonoma Counties.

Initiatives to get “good fire” back on the landscape have also created new opportunities for cultural burning and the incorporation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge into landscape management. The Amah Mutsun Land Trust has been partnering with agencies and other organizations to bring indigenous stewardship back to the Amah Mutsun Tribe’s traditional territory. They have been collaborating with Pinnacles National Park since 2006 and, in 2011, they were able to implement the first burn for cultural purposes in their territory in over 200 years. The Amah Mutsun Land Trust has since partnered with other organizations to introduce cultural burning in other areas, such as Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District’s preserves and the San Vincente Redwoods preserve managed by the Sempervirens Fund and Peninsula Open Space Trust. The Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria (FIGR) are another Tribe that is reintroducing cultural burning and other indigenous stewardship practices into the management of their traditional territory by partnering with organizations such as Audubon Canyon Ranch. In 2021, FIGR and the National Park Service entered an agreement to co-manage Point Reyes National Seashore, which will promote the reintegration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge into the stewardship of this traditional Coastal Miwok territory.

Stakeholder Perspectives

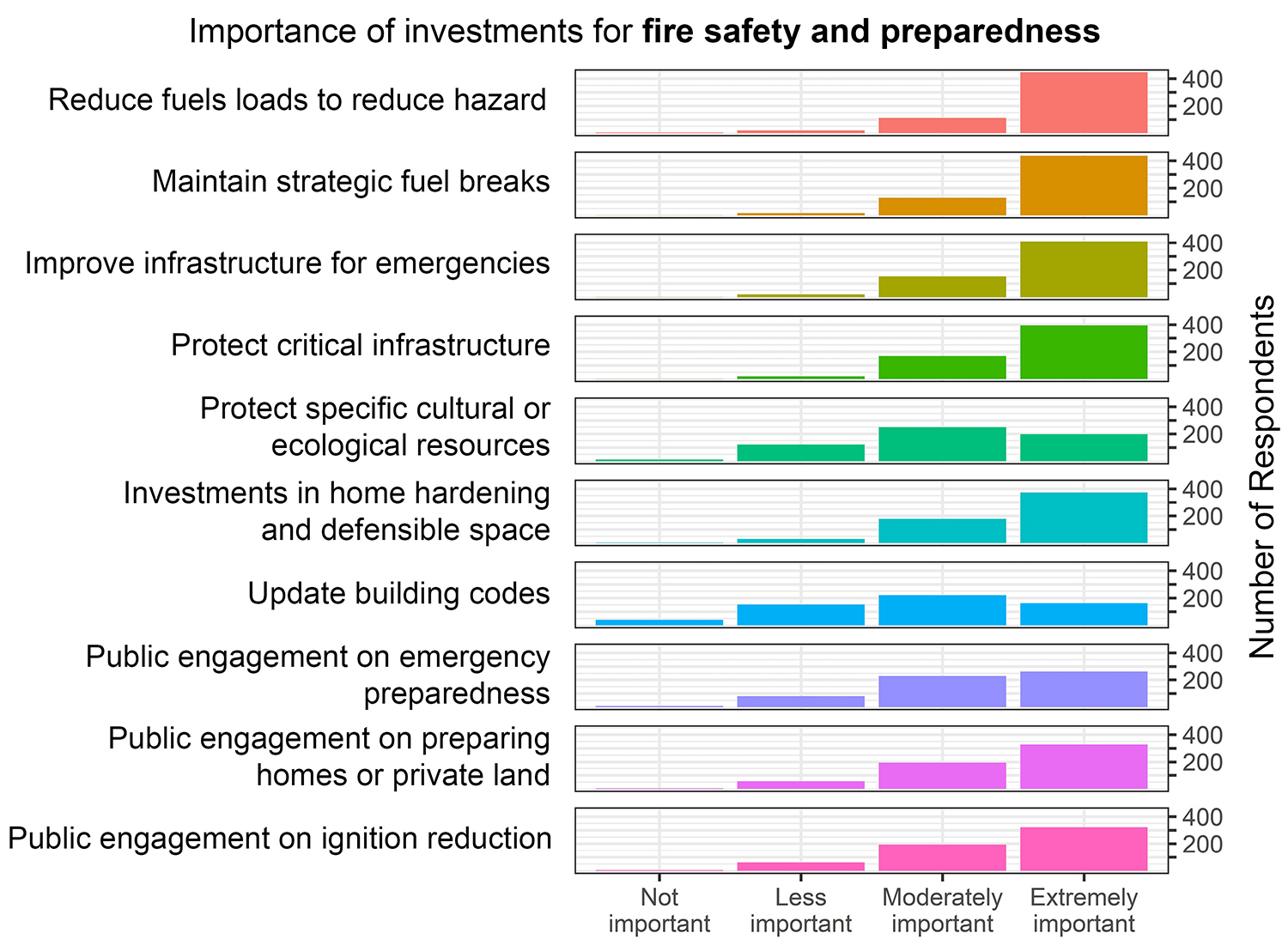

Reducing fuel loads and maintaining strategic fuel breaks, closely followed by improving infrastructure and protecting critical infrastructure, were all considered to be the most important areas of investment for increasing community safety and preparedness. Investments in home hardening and defensible space were also perceived to be highly important. There appeared to be less of a consensus on the importance of protecting specific resources and updating building codes.

Interview findings: When asked about the key issues related to community resilience to wildfire, many interviewees expressed safety concerns related to land development patterns and insufficient infrastructure, such as road access, for emergency response. Because wildfires were not historically considered a concern in this region, many communities developed in forested areas with steep topography and narrow roads. There are now efforts to make these communities more fire-adapted, but much more work needs to be done on private property, such as home hardening and defensible space. Several interviewees noted that there are limited resources to support this work because of restrictions on using public funding to benefit private property. As solutions to increase community resilience, interviewees recommended developing incentives for private property owner actions and increasing public engagement to help residents understand how they can take actions to protect their property and community.

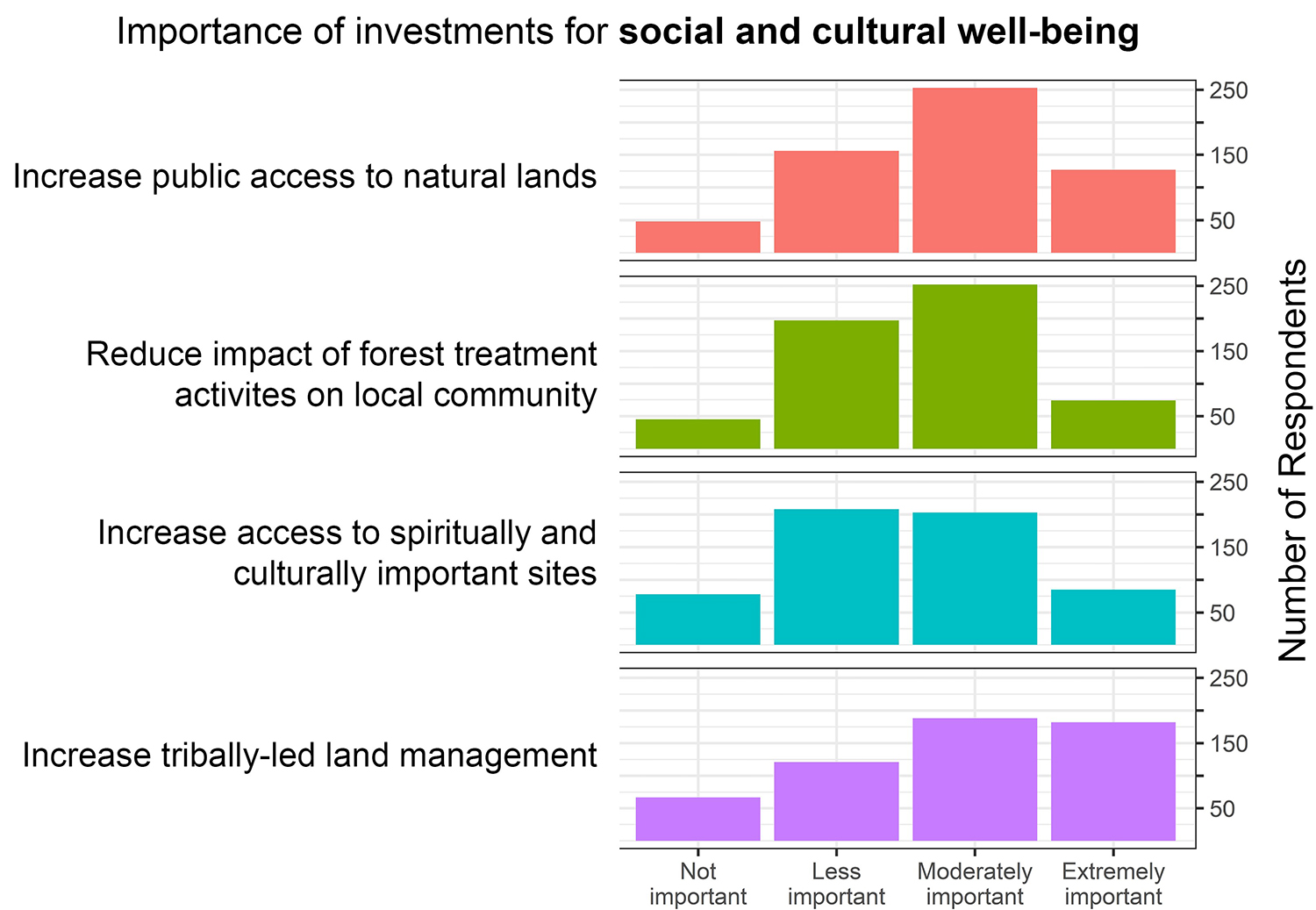

Survey respondents were also asked to consider investments focused specifically on social and cultural well-being. All potential areas of investment for increasing community well-being were rated on average as less than moderately important. However, increasing tribally-led land management, followed by increasing public access to natural lands, was on average rated slightly higher and had a higher response rate of ‘extremely important.’

Interview findings: Many interviewees highlighted how Indigenous land stewardship practices were instrumental in shaping the landscape of the Central Coast that we see today and how the suppression of cultural burning disrupted historical disturbance regimes. New partnerships with Tribal communities are reintroducing cultural burning and increasing tribally-led land management on public and private lands. However, one interviewee noted that grant funding constraints, including project deadlines and metrics focused on acreage treated, can be barriers to engaging and integrating Tribes into decision-making and land management processes.

Resource Conditions

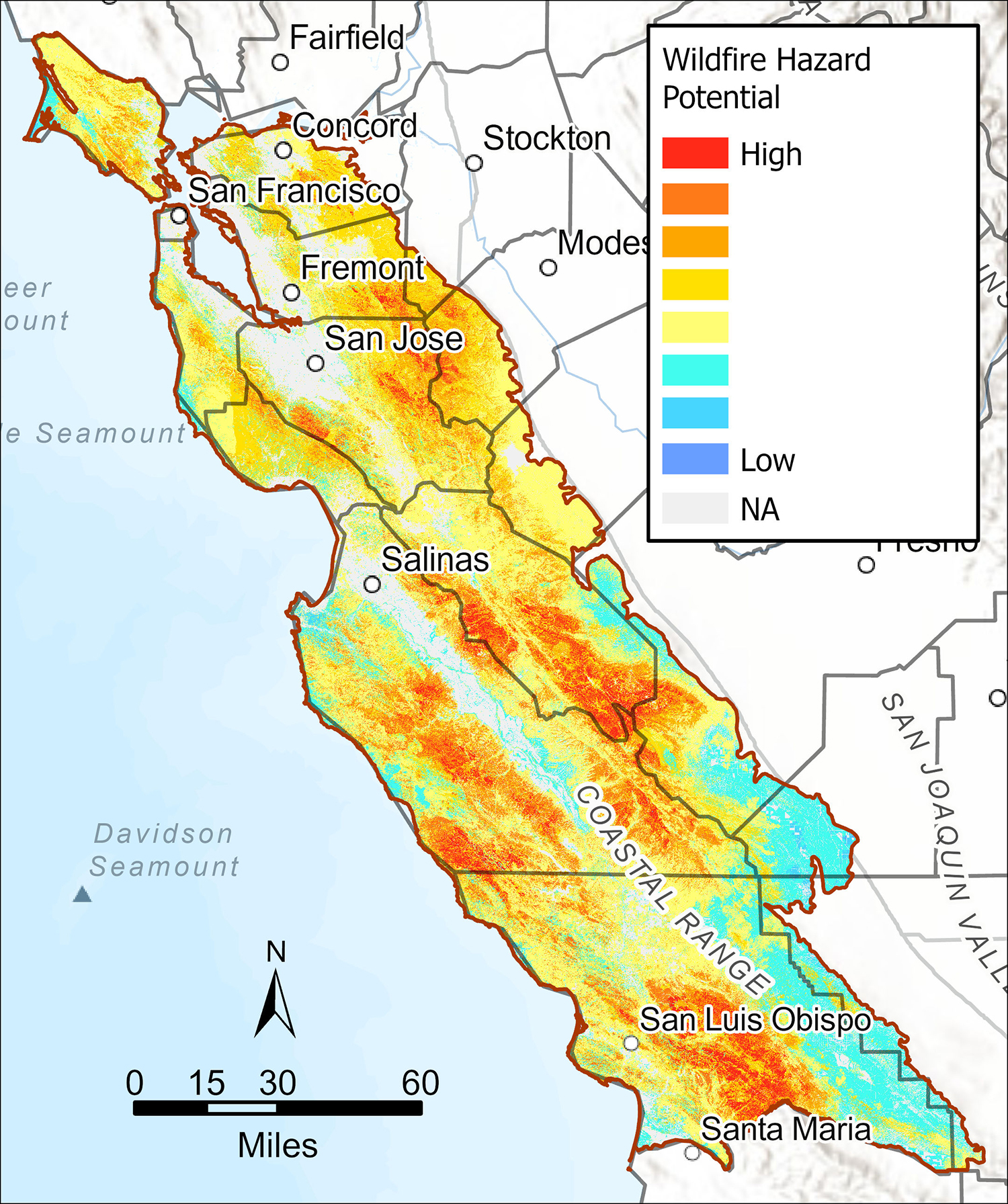

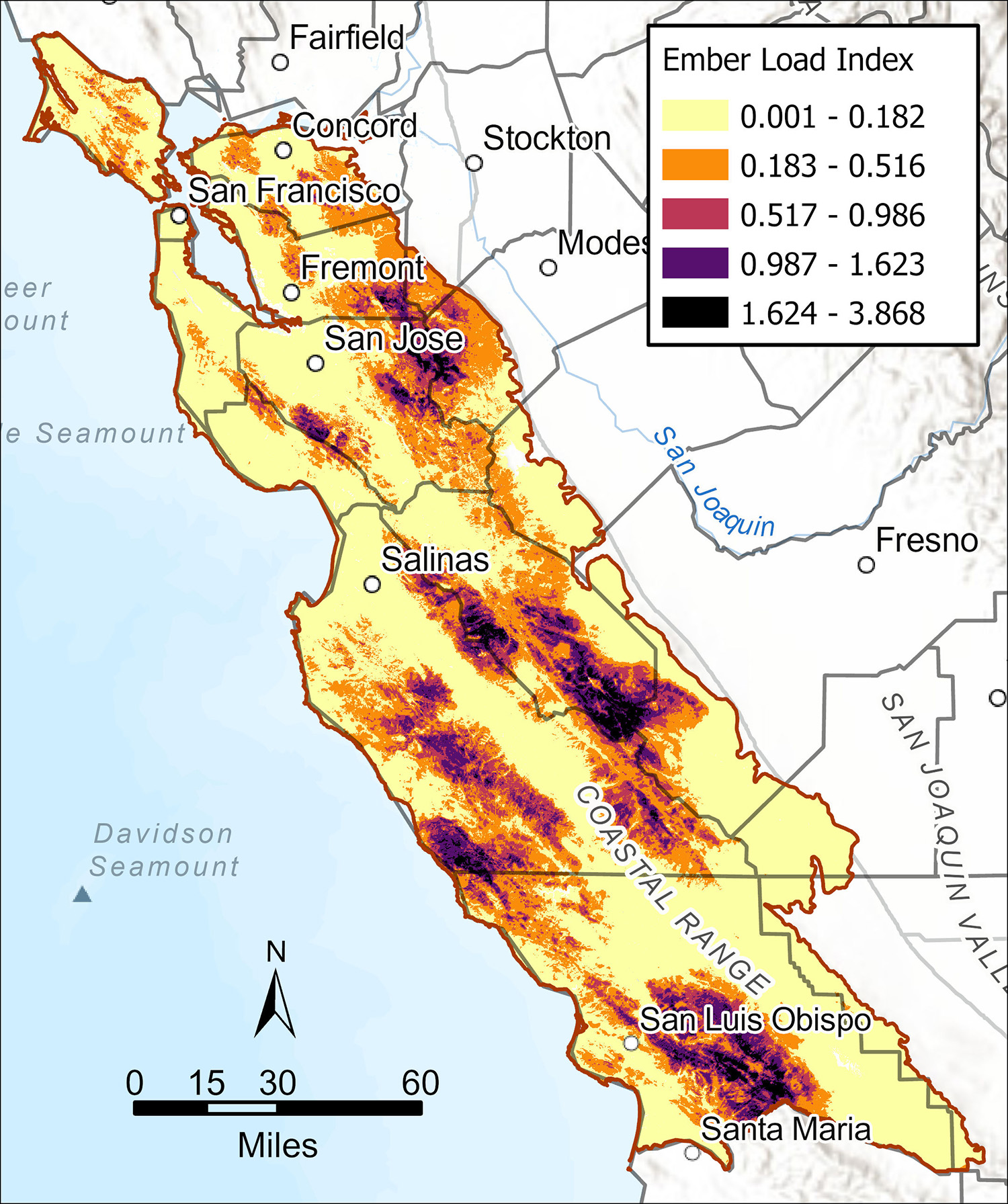

To support and create fire-adapted communities, we must understand the threats a community faces from wildfires. Measuring wildfire hazard potential (top) can help prioritize locations of fuel treatments. In the Regional Resource Kit, this metric focuses specifically on potential for fires that may be difficult for suppression operations to control. High potential for wildfire hazard exists in all of the Central Coast counties. Hazard potential is especially high and concentrated in southern San Benito, Monterey, and San Luis Obispo Counties. During a wildfire, embers often spread the fire, potentially carrying it from wildlands and into communities. Source of ember load to buildings (bottom) is a relative index metric that incorporates burn probability, local vegetation and topography, as well as models that track the travel of embers from sources to downwind areas. The resulting map layer shows relatively how many embers are predicted to land at a location with buildings. Areas along the wildland-urban interface tend to be at especially high risk of exposure to embers. Understanding how embers are likely to spread during a fire and the amount of embers that may be carried can help communities prioritize where investment in building hardening is needed to resist ignition.